At first glance, the GitHub Universe badge reads like playful swag, a full color screen with a few built-in games and a clever little Tamagotchi. What it quietly does that matters right now is run as a standalone, battery-powered, WiFi-enabled printed circuit board with accessible general-purpose pins that you can solder to and program.

The real significance here is not that a badge plays Flappy Bird. The detail that changes how this should be understood is that modern conference badges are now complete hackable IoT nodes. That shifts them from ephemeral tchotchke to a rapid prototyping platform that joins cloud identity, a small screen UI, and direct physical control of peripherals.

What most people misunderstand is that a conference badge isa simple novelty. It is not. It is a constrained computer, and those constraints define what you can do with it. This article reveals how one attendee turned a GitHub Universe Badge into an addressable LED controller using MicroPython, why that hack matters, and which limits will bite before the novelty wears off.

What The Badge Actually Is

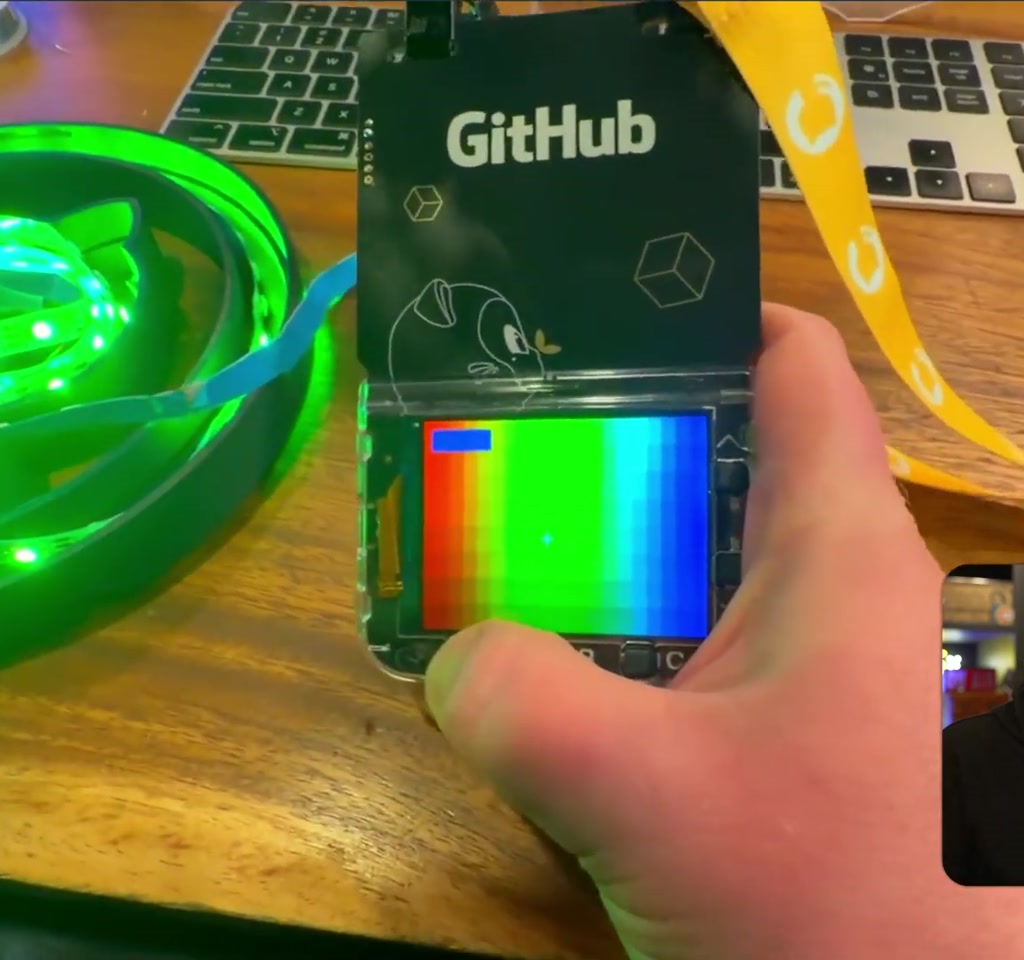

The device shown at GitHub Universe is a printed circuit board with built-in wireless radios, an antenna, a color display, and exposed pins for power and IO. It ships with small apps on the device that include a Tamagotchi, an Etch A Sketch, Flappy Bird, and a badge app that can pull your GitHub profile when you connect the badge to WiFi.

The badge runs code directly on the device and supports MicroPython. That means you can upload Python-style scripts, handle button events, and draw on the screen without a full desktop toolchain. For a developer used to web stacks, that lowers the friction of moving into hardware.

Why This Feels Like A Tiny IoT Computer

What becomes obvious when you look closer is that the board contains elements you would expect in a small IoT node. It has WiFi and Bluetooth, a battery connector for portability, and general-purpose IO pins exposed along the edge. Those pins are not decorative. They permit powering and controlling external hardware such as addressable LEDs.

The badge is portable, battery-powered, and online. That alone is the architectural shift. It is a pocket-sized agent that can host a UI, fetch identity from the cloud, and then directly toggle physical outputs. That combination is what changes the use case from collectible to platform.

How The Badge Was Hacked Into Addressable LEDs

At the conference, the speaker paired the badge with a small 3D printed light assembly that held addressable RGB LEDs in a strip. The light assembly expected a microcontroller module such as an ESP32, but the badge already offered power and GPIO pins, so the hack was to connect the pixels directly to the badge.

The basic wiring approach was simple. Use the badge 3.3 volt output for power, connect ground, and use one of the badge GPIO pins as the LED data line. Because some solder joints break under stress, the builder reflowed and resoldered where needed before testing the code.

Hardware Pins And Voltage Realities

The badge exposes a 3.3-volt rail and multiple GPIO pins. The LED assemblies supplied at the conference are 5-volt addressable pixels that accept a power line ground and a single data line. That presents two practical realities.

First, some LED strips will run when supplied with 5-volt power even if the data line is driven from 3.3-volt logic, but this is not guaranteed. Logic level mismatch is a real constraint. If you plan on long runs of pixels or guaranteed reliability, you should expect to add a level shifter or use a power rail that matches the pixel specification.

Second, individual addressable RGB pixels can draw significant current at full brightness. A common rule of thumb is roughly 60 milliampere per pixel at full white. That means 10 pixels can draw close to 600 milliampere, and 30 pixels can approach 1.8 ampere. Powering tens to hundreds of pixels will push the battery and the badge power supply well beyond what is safe for on-board regulators.

The MicroPython Software Play

The badge runs MicroPython-style scripts. The builder wrote a small utility to address the individual LEDs because the typical NeoPixel library was not present on the device image by default. Implementing a minimal driver in MicroPython is feasible, but it exposes two constraints.

Memory and timing are constrained on small microcontrollers. Bit-banging the data line from Python-style code can work for short strips, but may struggle as the number of pixels grows. And because some convenience libraries are missing, you must be ready to implement lightweight drivers or strip down features to make everything fit in the available RAM.

What The Hack Actually Did In Practice

Once wired and running, the badge hosted a small UI that let the user pick a color with a cursor. A single button press pushed that color into an array and lit specific pixels. Triggering multiple presses cycled modes, and after five presses, the system went into a diffuse rainbow mode across the pixels.

The visual effect is not a single sharp point of light but a diffuse, pleasing rainbow that plays well against the badge screen. The project demonstrates a simple interaction loop that turns a tiny UI into a physical effect in the world.

Two Concrete Constraints That Will Define Your Project

The first constraint is power. Portable badges are designed for low duty cycles. Driving addressable LEDs at high brightness turns the battery into the limiting factor. Expect the runtime to drop from many hours into a window of a few hours or less, depending on LED count and brightness. For reference, a strip of 30 pixels at full white will often draw near 2 amperes, which is a dramatic load for a tiny battery and the badge power regulator.

The second constraint is software resource limits. The badge runs a compact firmware image. That means some convenience libraries, like a full NeoPixel implementation, may be missing, and you will likely need to write a minimal timing-sensitive driver. The tradeoff here is speed and convenience versus control and portability. Implementing your own light driver often works, but it adds development time and can be sensitive to timing jitter when WiFi or other interrupts occur.

Power and software combine to produce a practical ceiling. People can prototype with a handful of pixels for demonstrations. Pushing past tens to hundreds of pixels requires external power sources and careful software architecture, or moving the heavy lifting off the badge to a dedicated microcontroller.

Practical Risks And Adoption Friction

Soldering to a badge is a pragmatic choice for hackers, but it introduces failure modes. Solder joints can break under flex, connectors can fail, and modifications will almost always void any warranty. The speaker literally pulled a badge from the garbage to experiment. That anecdote underscores a cultural constraint for newcomers. If you intend to hack badges, budget for replacements and accept that some units will be sacrificed.

There is also a learning curve. Moving from JavaScript and web stacks into embedded IO and power management requires crossing electrical and thermal thinking. The badge lowers the entry barrier with MicroPython, but learning the constraints of voltage, current, and timing remains necessary.

Who Makes These And How To Think About Sourcing

The conference speaker identifies the hardware as being made by a company the speaker calls Pimarini and says similar badge packages are sold to conferences. Whether you buy a developer kit for experimentation or obtain one as swag, the important part is that these boards are increasingly available to tinkerers who want a compact, connected platform.

If you want to learn more about addressable LED behavior before soldering, Bit Rebels has covered the basics of addressable LEDs and power management in prior stories. Reading up on expected current draw will save time when you reach for a multimeter.

Where This Sits In A Wider Trend

From an editorial standpoint, the badge hack is a symptom of a larger shift. Physical conference swag is migrating from passive memorabilia to an accessible hardware interface for makers. That matters because it lowers the barrier for software developers to learn real hardware constraints and to iterate on physical products without buying an entire lab.

The other cultural change is the speed of iteration. With a WiFi-enabled badge, you can fetch identity from the cloud, display it locally, and then tie that identity to a physical output in seconds. That speed is powerful for on-site demonstrations and for building interactive art and proof of concept prototypes.

Concrete sensory detail: when the rainbow mode runs on the small 3D printed dome, the light diffuses across the plastic, and the badge display still updates responsively. It looks less like a hacked toy and more like a coherent system that communicates state both visually and digitally.

What To Try Next And Why It Matters

The speaker asked whether the badge could be hooked up to a previous robot vacuum project. That idea is far from silly. The badge can be a compact human interface for a robot, showing status, accepting commands, and bridging networked identity to local control. The tradeoff is that a robot will typically need robust, continuous power and low latency. For anything beyond simple commands, dedicating the heavy lifting to a proper microcontroller or a companion board will be the pragmatic path.

From a practical experimentation standpoint, try these incremental steps. First, wire a small five to ten-pixel strip and validate the current draw at moderate brightness. Second, implement a tiny MicroPython driver and limit update rates to avoid timing contention. Third, separate power for larger strips to avoid overtaxing the badge regulator. These steps isolate risk and let you learn the platform without destroying hardware.

One quoteable idea to leave you with is this. Conference badges are no longer souvenirs. They are compact, connected laboratories you can afford to break. That is why hacking them feels like a new kind of fast prototyping that matters for makers and designers alike.

There is a temptation to treat every successful demo as a finished product. The real challenge comes when you decide to scale color count, runtime or reliability. Those are the points where the simple hack becomes a systems problem and where engineering choices determine whether the idea is a demo or a deployable feature.

If you plan to try this, respect the constraints. Budget for external power when you exceed a few dozen LEDs, add level shifting when you interface 5-volt pixels, and keep your software minimal if you want responsive behavior. These are not obstacles to creativity. They are the design space.

Looking ahead the most interesting consequence is cultural. As more conferences hand out programmable, connected hardware, the next generation of prototypes will start on event floors. That changes who learns hardware and how quickly those lessons propagate across communities.

If you want to explore similar projects, keep an eye on maker-focused hardware that exposes pins and runs a friendly runtime. The convergence of small screens, identity integration, and low barrier programming is making a new kind of hardware prototyping possible. The badge is proof and an experiment at once.

COMMENTS