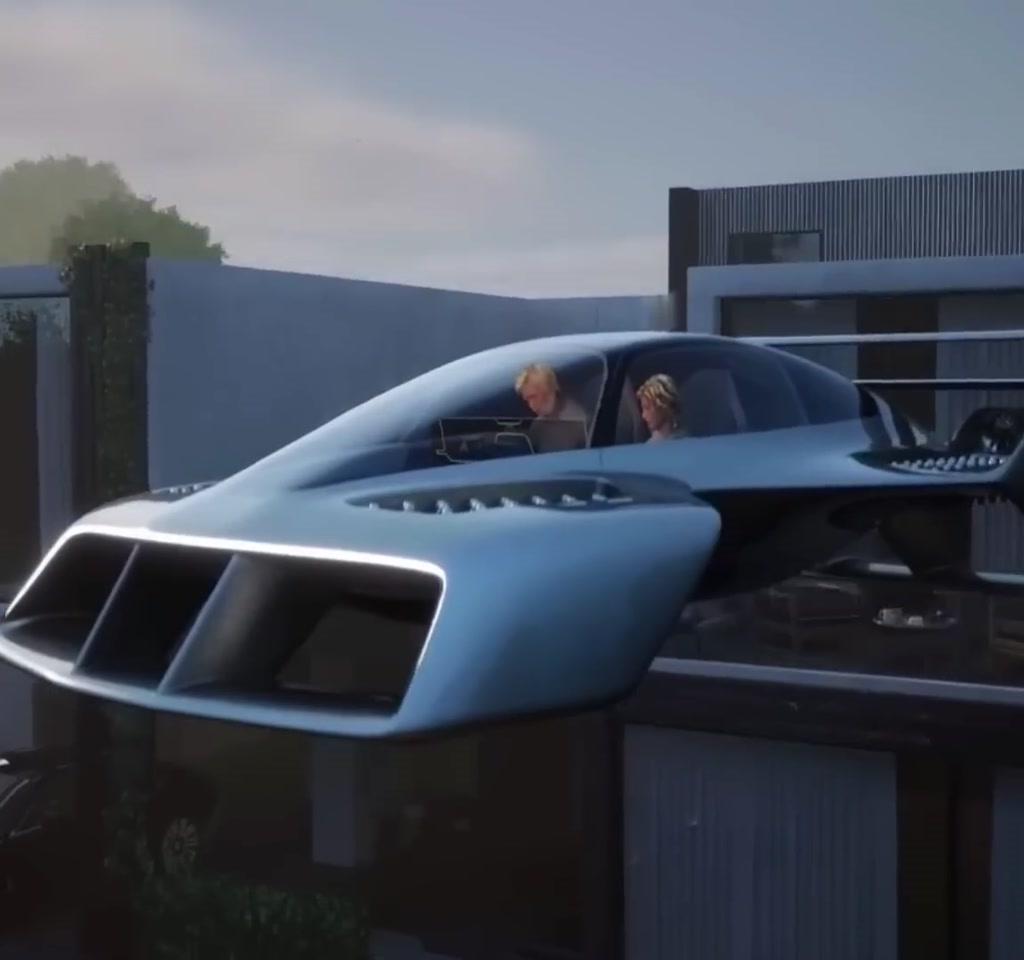

The LEO Coupe landed in the public imagination like a plot twist in a near-future thriller. It is both a hypercar-shaped object and a vertical takeoff personal aircraft, announced by a small team who say it will fit in a two-car garage, fly straight up like a drone, and cruise at jet speeds. That combination of everyday footprint and extraordinary capability is why this matters now.

The real significance here is not merely that it can fly. What changes the conversation are the engineering choices that attempt to reconcile garage parking, short runway independence, and a level of redundancy usually reserved for much larger aircraft. If those pieces line up, the LEO Coupe could make vertical takeoff and landing practical for private owners, not only fleet operators.

Most people misunderstand flying cars as single breakthroughs rather than systems problems. The moment this becomes interesting is when design, propulsion, controls, charging, and regulation are treated together. LEO Flight, the startup behind the project, is presenting precisely that systems approach: compact dimensions, 100 electric jet turbines hidden in the wings, integrated fly-by-wire controls, and a focus on redundancy and safety that defines this electric flying car concept.

By the end of this article it will be clear what the LEO Coupe actually reveals about the future of personal flight, and what political, technical, and economic constraints will determine whether it stays a niche object of fascination or becomes a daily transportation choice.

Who Built The LEO Coupe

LEO Flight started as a small, design-forward team formed during global lockdowns. The founders named in public briefings are Pete Batar and Carlos Salath. According to the company narrative, Batar brings experience from Electric Jet Aircraft-related work and jetpack systems, and Salath comes from an automotive design background.

That origin story matters. This is not a megacorp skunkworks project where supply chains and production scale are prequalified. It is a lean team trying to combine aerospace-level engineering with automotive desirability and usability. That shapes priorities and tradeoffs: the compact footprint and visual design are deliberate choices to make a vehicle people would want to park in a garage, not just fly from a field.

How The Electric Flying Car Works

At the heart of the LEO Coupe is an unusual propulsion strategy: one hundred small electric jet turbines embedded inside the wings and forward surfaces. Those micro turbines provide vertical thrust for takeoff and then reorient or augment thrust for forward flight. The approach emphasizes redundancy and makes the vehicle behave more like a multirotor aircraft during takeoff, then like a jet in cruise.

The architecture blends drone concepts with aerospace controls. Enclosed jets avoid exposed rotors, improving ground handling and aerodynamic cleanliness, while full fly-by-wire steering and semi-autonomous flight aids let pilots command the vehicle through simplified inputs rather than analog stick work.

Control And Automation

LEO Flight describes the control interface as designed for accessibility: semi-autonomous flight features, auto stabilization, auto takeoff and landing, and what the team calls a game controller-style input for human command. This is the same pattern that has made advanced electric cars approachable for non-professional drivers, except applied to vertical flight where the margin for error is smaller.

Propulsion Tradeoffs

Using 100 turbines is a specific design tradeoff that prioritizes redundancy. The company argues that losing one or two jets should not compromise safety. The tradeoff is complexity: more moving parts, more inspection points, and a different maintenance regime than a single-engine aircraft.

Performance Claims And Practical Limits

LEO Flight has shared headline numbers that read like a wish list for commuters: a top speed of 250 miles per hour, a cruise speed of roughly 200 miles per hour, a range of about 250 miles, and flight time of over one hour per charge. Charging is said to work with standard EV home outlets and fast chargers.

Those figures are compelling, but they immediately raise two operational constraints that will determine real-world usefulness.

First constraint, energy and battery limits. One hour of flight and a 250-mile range imply a very high sustained power draw during vertical takeoff and cruise. Given current battery energy densities, the vehicle will need a substantial battery pack that adds weight. That weight is the threshold that drives tradeoffs between payload, range, and recharge time. Recharging from a home charger is realistically measured in hours rather than minutes, and repeated daily flights will demand fast charging infrastructure or battery swap strategies to avoid long downtimes.

Second constraint, cost and maintenance. A propulsion system made of 100 turbines increases inspection and part replacement points compared with a typical electric car. Even with redundancy built in, maintenance frequency tends to scale with the number of moving parts. That tends to shift operating costs into the hundreds of thousands over a vehicle lifetime rather than the tens of thousands many people expect from consumer EV ownership. Initial purchase price is likely to be in the high-end consumer bracket, making early adoption concentrated among wealthy private owners and specialized fleets.

In short, the LEO Coupe’s performance targets are technically plausible when prototyped, but the boundaries of energy, charging, and upkeep will define whether the vehicle is a weekend toy or a daily commuting tool.

Safety, Redundancy, And Emergencies

LEO Flight emphasizes layered safety systems. The package includes redundancy through many turbines, automatic stabilization, auto takeoff and landing, emergency glide modes, and a ballistic parachute system that can lower the entire vehicle. There are also claims of emergency airbag systems and the ability to land on water in an emergency.

What actually determines whether safety is convincing is not just hardware redundancy but the systems and certification around it. Redundancy buys time and options, but it does not remove the need for reliable diagnostics, consistent maintenance cycles, and fail-safe modes that are certified by aviation authorities.

Redundancy Versus Complexity

Here is a tension worth stating plainly. Redundancy reduces single-point failures, but it raises the burden of monitoring and maintaining many components. That creates operational costs and inspection cycles that will influence insurance, pilot training requirements, and the likely buyers who find the value proposition attractive.

Certification And Pilot Training

Certification pathways for new aircraft architectures are conservative by design. The LEO Coupe will need to be integrated into existing regulatory frameworks or new frameworks must be created. That introduces a timeline friction often measured in years rather than months. Pilot training is another axis: semi-autonomous aids reduce the skill floor, but regulators will still require verified competency for private pilots operating in urban airspace.

Who Will Buy One And Why It Matters

LEO Flight positions the Coupe as a private owner vehicle, not just an air taxi. Potential markets include private commuters who can afford the premium, tourism operators, emergency responders in remote areas, and specialized commercial services. The design language makes a statement too: gull-wing doors, a floating pilot seat, and a look that mixes hypercar and spaceship aesthetics are intended to make ownership aspirational.

From an editorial standpoint, the most interesting implication is cultural. Personal flight that fits in a garage changes how city space is valued. Roofs, private yards, and small lots become nodes in a three-dimensional transport network. That in turn changes urban planning conversations about density and infrastructure.

There are clear adoption friction points. Regulation, noise ordinances, vertiport locations, and local traffic management will shape where these vehicles can operate. Even if the technology scales, social and legal acceptance will shape use cases more than raw performance metrics.

Prototypes, Timeline, And The Road To Production

LEO Flight reported rapid prototyping early on, claiming three prototypes in under six months. One drone variant, cited as ArcSpear, reportedly achieved 100 miles per hour during flight tests and functioned as a testbed for flight control systems. The LX1 is described as a full-size manned prototype with both forward and vertical jets and is undergoing flight testing. The company has suggested a production vehicle could arrive around 2027.

Timelines like this are a mix of engineering ambition and regulatory reality. Building a manned prototype is a crucial milestone that demonstrates feasibility. The practical limit will be integration into certified production, supplier scaling, and the creation of a maintenance and service ecosystem. Those elements typically add years and millions of dollars to a roadmap.

Where This Fits In The Broader Shift Toward Urban Air Mobility

LEO Coupe is part of a larger industry conversation about urban air mobility. That field includes electric vertical takeoff and landing vehicles, autonomous air taxis, and hybrid aircraft designed for short urban hops. What distinguishes LEO Flight is the combination of a street-style footprint and a claimed performance envelope that crosses the line from short hops to meaningful intercity range.

Infrastructure And Noise

Noise is often overlooked in headlines. Even quiet electric jets create different acoustic signatures than cars. Communities will weigh those differences when deciding on vertiport placement. The tradeoff is clear: access closer to riders increases convenience and value, but it also concentrates noise and raises approval barriers.

Air Traffic Management

Scaling beyond a handful of vehicles requires a low-altitude traffic system that is safe and predictable. That system will likely involve geo-fencing, digital permits, and coordination between local authorities. Expect initial deployments to be highly localized until national or regional frameworks mature.

LEO Coupe Vs Alternatives

For buyers and planners deciding where to invest, the comparison matters. LEO Coupe presents a unique mix of personal ownership design and high claimed performance, but it sits alongside eVTOL air taxis, hybrid short takeoff aircraft, and multirotor drones that have different tradeoffs in capacity, noise, and infrastructure needs.

Vs eVTOL Air Taxis

Air taxis prioritize fleet operations and centralized vertiports. They often accept shorter ranges and heavier regulatory oversight in exchange for predictable service routes. The LEO Coupe aims at private ownership and longer range, shifting the burden of maintenance and charging onto owners rather than operators.

Vs Hybrid And Conventional Light Aircraft

Compared with hybrid or piston light aircraft, the LEO Coupe emphasizes vertical takeoff and redundancy rather than fuel efficiency per mile. That yields urban access benefits but raises energy and maintenance costs compared with fixed-wing aircraft operating from runways.

Two Concrete Tradeoffs To Keep Watching

First tradeoff, energy density versus practicality. The claimed one-hour flight and 250-mile range are exciting, but they place the LEO Coupe in a narrow energy window that will require either heavier batteries or conservative operating profiles. In practice that means shorter effective range under real-world conditions, or the need for extensive charging infrastructure to sustain regular use.

Second tradeoff, redundancy versus maintenance cost. The 100-turbine architecture increases in-flight safety through redundancy, but it multiplies inspection and replacement points. That shifts the ownership model toward higher ongoing costs and a specialized service network. Early adopters may accept that, but broader consumer adoption will need predictable, affordable maintenance cycles.

Who This Is For And Who This Is Not For

Who This Is For: Wealthy private owners seeking rapid point-to-point mobility, operators in tourism and remote response, and experimental commercial services that can absorb higher maintenance costs. The Coupe is tailored to buyers who prize convenience, design, and performance over low running costs.

Who This Is Not For: Budget commuters, mass transit planners, or buyers seeking minimal maintenance burden. Without broad charging infrastructure and lower service costs, the LEO Coupe is unlikely to be a near-term solution for everyday commuters in most cities.

Closing Thoughts

The LEO Coupe is not simply a prototype of a flying car, it is a design experiment that tests whether redundancy, compactness, and consumer-grade controls can coexist in a single vehicle without surrendering safety or range. What it reveals is less a guaranteed future and more a map of tradeoffs that cities, regulators, and buyers will negotiate.

Keep an eye on how the company addresses maintenance cadence and fast charging, because those two variables will determine if garage-to-runway trips are a rare spectacle or a routine commute. The LEO Coupe surfaces the future of urban mobility as a negotiated outcome between technology, regulation, infrastructure, and social acceptance.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

What Is The LEO Coupe? The LEO Coupe is a compact vertical takeoff personal aircraft developed by LEO Flight, using 100 small electric jet turbines, claimed cruise speeds around 200 to 250 mph, and a marketed range near 250 miles.

How Does The LEO Coupe Take Off? It uses one hundred micro turbines embedded in the wings and forward surfaces to provide vertical thrust for takeoff, then reorients or supplements thrust for forward flight.

What Is The Claimed Range And Speed? Public figures claim a top speed near 250 mph, cruise around 200 mph, and a range of approximately 250 miles or over one hour per charge; those are company claims and subject to real-world variables.

Can You Charge The LEO Coupe At Home? The company states charging works with standard EV home outlets and fast chargers, but real world recharge time is likely measured in hours and will affect turnaround for repeated daily use.

When Could Production Begin? LEO Flight has suggested a production vehicle could appear around 2027, but timelines depend on certification, supplier scaling, and regulatory approvals, which can extend schedules.

Does The LEO Coupe Require Pilot Training? Semi-autonomous aids reduce the skill floor, but regulators will still require verified competency and likely specific training for operating in urban airspace.

How Safe Is The 100 Turbine Design? The many turbines provide redundancy that reduces single-point failures, but the approach increases maintenance and monitoring requirements. Safety depends on both hardware redundancy and certified systems, diagnostics, and maintenance regimes.

Is The LEO Coupe Street Legal Or Certified? Certification and legal operation depend on aviation authorities and local regulation. The transcript indicates certification pathways are still a major constraint and timelines will be measured in years rather than months.

COMMENTS