ATLAS is presented as a superhuman robot built to perform and built to work. That claim matters now because the conversation has shifted from spectacle to service.

The transcript that accompanies ATLAS is short on specifics but heavy on intent. For five years the creators say they have been taking robots out of the lab and into the world. The real significance here is not only that a machine can jump, run, climb, and flip. What actually determines whether this matters is how those capabilities translate into repeatable, safe, and cost effective labor outside carefully controlled demonstrations.

Most people assume a flashy robot means instant replacement for human effort. The part that changes how this should be understood is the practical tradeoffs. ATLAS stands at the intersection of possibility and constraint. The promise is wide. The places it can deliver value are narrower, at least for now.

ATLAS As A Proof Of Capability

The public narrative around ATLAS emphasizes three decades of pushing boundaries, then a recent five year push to move robots out of pure research and into everyday tasks. That arc matters because it signals a shift in priorities from exploring what is possible to asking what is useful.

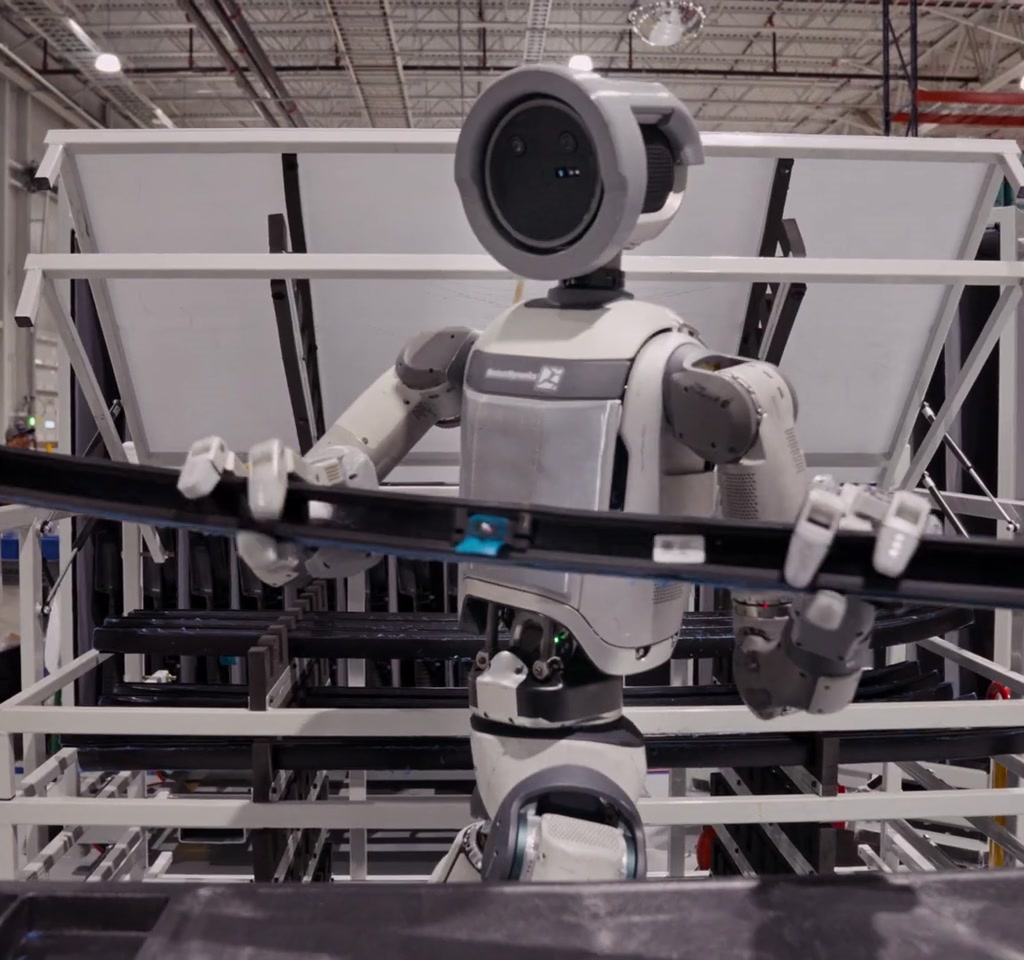

What becomes obvious when you look closer is that many of the breakthroughs showcased are about mobility and manipulation. Engineers gave machines legs, arms, and hands because the physical world rewards dexterity and balance. Walking over uneven ground, stepping up and down, holding tools, and adjusting posture while exerting force are still hard problems for robots. Demonstrating them is the technical milestone. Turning them into reliable work systems is the next challenge.

From an editorial standpoint, ATLAS is less a final product and more a bridge. It connects three decades of lab knowledge with the more mundane requirements of logistics, inspection, and field service. That bridge does not guarantee wide adoption. It exposes how tight the gap remains between a convincing demo and an economic tool.

From Lab Demos To Actual Jobsites

Stunts are persuasive. They show what will be possible when robotics engineering meets messy reality. But a jobsite or a warehouse is not a stage. Those environments demand reliability, predictable uptime, interoperability with existing equipment, and operators who can supervise or intervene quickly.

What most people misunderstand is that transitioning from controlled demonstrations to commercial deployment multiplies constraints rather than removing them. The same features that make a demo memetic, like agility and expressive movement, also add points of failure. Joints that allow a flip also require sensors, actuators, and control software that can fail under prolonged or repetitive stress.

Two Hard Limits That Decide Success

The path to usefulness is shaped by a few simple tradeoffs. If those tradeoffs are not acknowledged, promises outpace reality. The two limits that will determine where ATLAS actually matters are cost and operational endurance.

Cost And Deployment Tradeoffs

Cost is the blunt instrument in every adoption decision. Public material does not list a retail price for ATLAS, but similar advanced research grade robots tend to sit well above ten thousand dollars. For practical applications the relevant threshold is whether costs fall into the tens of thousands or into the hundreds of thousands. For many industrial buyers the tipping point is being closer to the lower side of that range.

This is not just purchase price. Total cost of ownership includes training, service contracts, spare parts, and integration. Training an operator or a team to supervise a mobile humanoid often takes tens to low hundreds of hours of specialized instruction, which translates into several thousand dollars of upfront expense and ongoing labor. Integration with existing systems, like conveyor controls or safety lockouts, commonly produces additional engineering bills that are frequently measured in the low five figure range.

Power Safety And Maintenance

Power and maintenance create second order constraints that are easy to underestimate. Mobility and dexterous manipulation require significant energy. In practice this means operating cycles are often measured in hours rather than days. That forces logistics for battery swaps or tethered charging, which in turn changes how and where the robot can be deployed.

Maintenance is also where many robotics projects quietly fail. Moving parts and high torque actuators wear. Real world deployments reveal failure modes after repeated cycles. Mean time between repair often lands in the hundreds to low thousands of operating hours for early generation hardware. That is good engineering progress, but it also means downtime and spare part inventories must be planned for. Those are real costs that scale with fleet size.

Where ATLAS Actually Makes Sense

When designers talk about making life easier and safer, they are highlighting the types of jobs where humanoid mobility can be meaningful. Tasks to consider include inspection in environments not amenable to wheeled robots, repetitive material handling where a humanoid posture matches human designed tools, and emergency response scenarios where flexibility beats specialization.

Good early use cases have three characteristics. They are dangerous for humans, they require human like motion or tool use, and they are performed often enough to justify a non trivial investment. That last part is critical. A single costly deployment for an occasional task rarely pays back. The work must repeat at a cadence that turns a high capital cost into a lower per cycle expense.

Concrete examples of plausible fits include remote inspection of uneven infrastructure, where sending a humanoid can avoid a risky human entry, and structured warehouses with constrained areas where a human shaped robot can manipulate the same fixtures humans do. These are not universal answers but they show the logic of matching capability to context.

Where It Will Not Replace People Soon

Humanoid robots will not immediately replace humans in tasks that require broad judgment, improvisation, or social interaction. Many jobs require fast contextual decisions, nuanced dexterity, or a capacity for unpredictable social signals. Those remain human advantages because they are cheap to deploy and robust to edge cases.

What becomes clear is that humanoids will reassign tasks rather than remove work. Heavy lifting in constrained spaces, repetitive inspections in hazardous areas, and predictable physical chores are likely candidates for automation. Jobs that center on adaptability, relationship management, or high level decision making will continue to value human presence for the foreseeable future.

Constraints Summarized

Two concrete constraints to keep in mind are cost and endurance. Cost tends to push deployments toward high value, repetitive tasks because initial hardware and integration expenses typically scale into the hundreds of thousands rather than the tens of thousands. Endurance limits place operating cycles in the range of hours per charge, which forces either short term use cases or supporting infrastructure for charging and maintenance.

Those are not mere technicalities. They are the commercial variables that decide whether a lab demo becomes a workplace tool or an expensive curiosity.

Culture, Work And The Humanoid Image

The creators framing ATLAS as a companion and helper matters for public perception. Humanoid form factors are powerful cultural symbols. They imply parity with humans and trigger emotional thinking about replacement, companionship, and safety. From an editorial perspective, that image is a double edged sword. It helps people imagine the future, but it also sets unrealistic expectations about near term capabilities.

The smartest strategy may be to lean into the symbolic value while keeping deployments deliberately narrow. Use the humanoid form where it gives a measurable advantage over wheeled or static systems. Resist the temptation to treat the robot as a generalist until the economics and reliability justify that claim.

One paragraph worth quoting is this observation about the present moment: ATLAS proves that human like motion can be engineered, but it does not prove that human like work will be economical across the board. That distinction will decide which industries change quickly and which ones change slowly.

There are also regulatory and safety realities that will shape adoption. New standards for physical safety, insurance implications for automated labor, and workplace rules for human robot interaction are all likely to appear as real deployments scale. Expect regulators and insurers to demand performance data measured over hundreds to thousands of hours before they relax rules that protect workers and the public.

From a pragmatic standpoint, the first fleets will probably be small. Early adopters tend to pilot with one to a handful of units, measure outcomes for months, and then expand if metrics like uptime, throughput, and return on investment meet expectations. That pattern is familiar from other capital intensive technologies and it sets a reasonable timetable for broader adoption.

Looking Forward

ATLAS is a marker, not a destination. The creators describe it as the beginning of a tomorrow where physical automation expands human horizons. The responsible reading of that sentence is to accept both the potential and the friction. Robotics will change certain kinds of work first, and it will do so where economics, safety, and endurance line up.

What has changed is that the conversation has to move beyond capability theater. Real progress will be judged by whether these systems reduce risks, lower recurring costs, or enable new activities that were previously impossible. Those are measurable outcomes. They do not happen at once. They emerge as engineers, operators, insurers, and buyers converge on practical deployments.

For readers wondering what to watch next, track three things. First, the cost per deployed hour as systems leave pilot programs. Second, the mean time between repair as units accumulate operating cycles. Third, the kinds of environments where humanoid form factors are chosen over wheeled alternatives. Those signals will show if ATLAS is a transformative bridge or an impressive detour.

The future hinted at in the transcript is compelling because it mixes imagination with applied engineering. The unresolved idea worth staying with is this. Technology can hand us new tools, but whether those tools change how society works depends on where the math meets the messy demands of everyday life.

COMMENTS