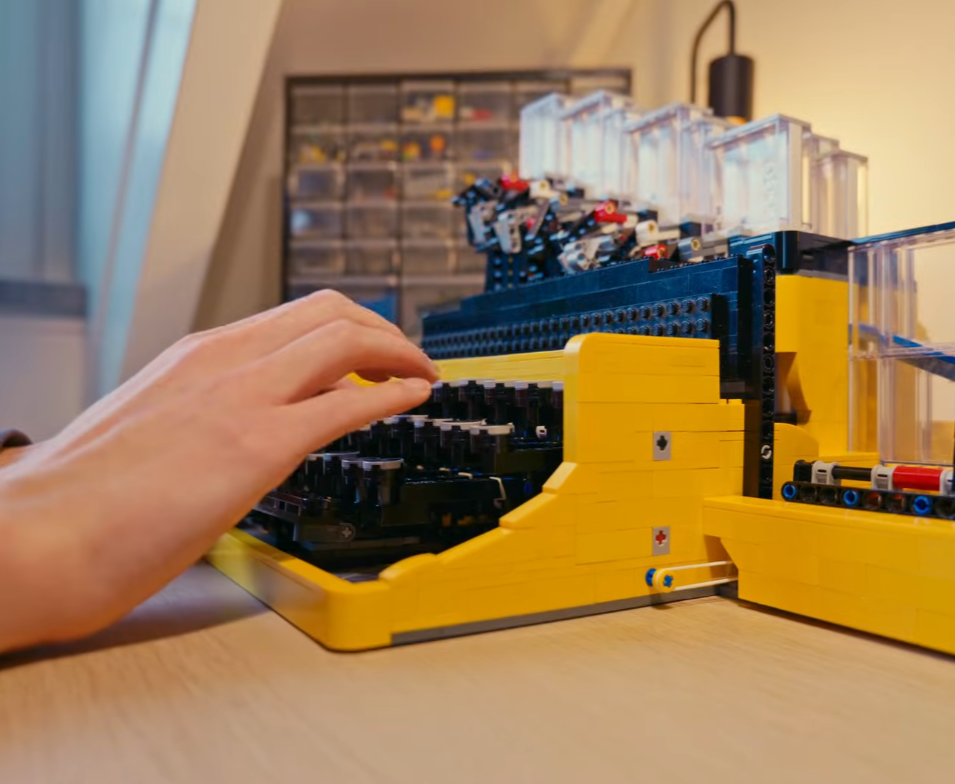

When LEGO released its mechanical typewriter set in 2021, the model nailed the look and the motion but stopped short of a simple promise: it could not actually type a letter back onto the bricks. That gap is the exact place one builder decided to start a new project, not by copying how typewriters use ink and raised type, but by rethinking what “typing” means when your only material is plastic studs and printed tiles.

The real significance of this redesign is not nostalgia for clacking keys. What actually determines whether a LEGO typewriter matters is whether the system can reliably place preprinted characters, aligned and oriented, onto a surface using only parts that exist in the brick ecosystem. The constraints of those parts force different engineering choices, and those choices reveal useful lessons for anyone designing mechanical logic from constrained components.

That shift in approach led the builder to three core moves: abandon ink and impact printing, make gravity the delivery engine, and solve orientation at the last moment with a purpose-found arch piece. Those moves turned a conceptual problem into a set of repeatable mechanisms, and they also exposed the tradeoffs that seal its practical limits.

What becomes obvious when you look closer is that the project is an exercise in tolerance and choreography. The machine handles 26 keyed inputs, gravity-fed magazines, a ramp that rotates tiles 90 degrees, rubber band tensioning for the press, and a carriage that must index exactly one stud per character. It works because each of those parts accepts narrow boundaries and then aligns with them.

Why The Official Set Couldn’t Transfer Type

Typewriters print by striking a raised character into an ink ribbon. LEGO tiles are flat decals, not raised metal type, so the original printing trick was off the table from the start. The designer behind this build recognized that constraint immediately and treated it as a design rule: if you cannot transfer pigment, you must transfer a preprinted mark instead.

That single reframing changes the entire engineering problem. The goal becomes placement, not impression. The unit of work is a 1×1 round tile clipped to a square plate, and the machine must dispense, orient, and press those tiles onto a white plate in the correct stud position and rotation.

Reinventing Printing Without Ink

Gravity As An Ally

Instead of a complex mechanism to punch or stamp, the builder used gravity to move characters. Each key dispenses a short ladder of identical tiles from a magazine. The tile falls down a ramp and is rotated by a small arch such that it ends up oriented correctly to be pressed onto the plate that stands in for paper.

This decision eliminated a second mechanism that would otherwise have to rotate or reorient pieces, cutting complexity at the cost of demanding more from the ramp geometry and the dispenser elevation.

The Orientation Trick

An otherwise small piece turned out to be pivotal. After many iterations, the designer discovered an arch-shaped element that reliably rotated the tile 90 degrees at the end of the slide. That single contact point converts an otherwise chaotic impact into a repeatable orientation step. It is an example of finding the right primitive in the parts archive and letting a simple interaction do the heavy lifting.

The ingenious pivot in this project is that it did not try to copy ink, it reinvented printing logic for bricks.

Key Mechanics: Dispensing, Pressing, And Carriage Movement

The physical typing motion became a two-step operation. Step one, pressing a key releases a tile and tensions a pusher via a beam and rubber band so energy is stored. Step two, when the key is released, the pusher slams the tile onto the plate. The carriage then needs to move horizontally one stud to prepare for the next character, and vertical movement advances the line height.

Several pragmatic subproblems emerged as tradeoffs during this work. For spacing, the keys initially sat too close and interfered on adjacent mechanisms, so the builder staggered rows instead of blowing up the machine footprint. For reloading, loose bricks worked manually but an automated reload beam proved unreliable and was removed in favor of a more trustworthy manual process.

Rubber Band Tensioning: Strength And Fragility

Rubber bands became the simple energy store across many mechanisms. They are cheap and compact, but they also compress loose brick stacks and pull on weak frames. The builder corrected compression by substituting half of the regular 1×1 bricks with slightly wider pieces that have a side stud, restoring spacing. Frame flex that reduced press force was fixed by reinforcing the rotating frame, and moving the rubber band anchor point improved timing and power.

Those are concrete tradeoffs: rubber band simplicity versus long-term mechanical certainty, and compactness versus the risk of compressed tolerances.

Constraints, Costs, And Time

This project makes clear that clever engineering does not erase practical limits. Two constraints are especially relevant.

1) Parts Availability And Cost. The builder opted for inexpensive round tiles clipped to plates because the only square 1×1 letter tiles LEGO made appeared in two sets that now both sell for roughly €50 each. To collect enough printed square tiles for ordinary typing would require multiple such sets and therefore jump into the low hundreds of euros. By contrast, the round tiles used for the magazine cost about €3 per pack, which kept the project affordable but introduced orientation challenges solved by the ramp and arch trick.

2) Time And Reliability. The machine was refined over roughly three months of work. Iteration time is a real cost here: the builder ran through many prototypes, a slow-motion camera discovery, and a week of subtle tuning before the full system became repeatable. Even now, the machine still shows occasional misfeeds and faint presses when a tile is not slammed firmly enough. Those are not catastrophic failures, they are thresholds you cross when moving from hobby prototype to practical tool.

Quantified context matters. The keyboard is 26 keys, the carriage must stop at single-stud intervals, and each line advancement requires manual reloading and a small paper roll adjustment. Those are operational constraints you would not accept in a daily writing tool but are perfectly coherent for a mechanical demonstration that proves a point.

What The Build Teaches About Constrained Design

There is a larger pattern here for makers and designers. When a canonical solution is blocked by a hard constraint, the productive move is to change the primitives rather than mimic the impossible step. By switching from impact printing to physical placement, the designer transformed an insurmountable problem into a sequence of simpler problems: dispense reliably, orient at a single point, press with stored energy, and index the carriage by studs.

The approach also underlines a practical engineering ethic: use parts in their strongest role. Gravity is free and reliable, arches rotate predictably, and rubber bands provide compact energy storage. The combination is not elegant in a textbook sense, but it is resilient and iteratively improvable.

Experience Signals And Editorial Take

What becomes obvious after studying the build is that small changes cascade. A single millimeter of frame flex changes press depth. A slightly steeper ramp improves reliability but increases required magazine height. The moment this system breaks down is almost always a tolerance issue, not a conceptual one.

That observation leads to an editorial judgement: the project is less about replacing keyboard technology and more about revealing how much mechanical complexity is hidden in everyday actions. A real typewriter tolerates human variance partly because it was manufactured to specific metal tolerances. Making the same behavior from mixed plastic parts and decades-old chain links yields a different set of tradeoffs, and those tradeoffs are the story.

The Limits That Define Its Usefulness

Two practical boundaries decide where this machine is useful. First, throughput and maintenance: typing a line requires periodic manual reloading and occasional corrections for misoriented tiles, so throughput is measured in minutes and iterations rather than in pages per hour. Second, accuracy and reproducibility: small misalignments and underpresses happen often enough that the device is best framed as a creative machine rather than a practical text production tool.

In short, the build succeeds up to the point where human patience and the physical limits of bricks meet. Within that window it is delightful, educational, and mechanically satisfying. Beyond it, the cost of smoothing every edge would rapidly escalate.

Where This Leads Next

The finished machine is a proof of concept with personality. It shows that mechanical logic can be rethought when a material forbids a canonical solution. For makers, that is the most valuable lesson: constraints invite new primitives and new interactions.

It also points to practical follow-ups. One could prioritize automation of reloads at the expense of footprint, or redefine the character set to reduce magazine complexity. Alternatively, substituting elastic energy stores for springs or experimenting with a guided, motorized carriage could trade charm for repeatability. Each change will highlight another tradeoff: cost, complexity, size, or reliability.

For now, the machine stands as an engineered answer to a provocative question: if LEGO’s set could not type, how hard is it to make bricks do the job? The answer is that it is doable, instructive, and bounded by very specific tolerances that define where the idea remains compelling.

Expect this kind of play between constraint and invention to show up more often in creative builds. The same design instincts that turned a flat-tile problem into a functioning printer apply across projects where the material defines the rules. That is where the next experiments will be most interesting.

For a closer look at the builder’s method, the slow-motion moments that unlocked the orientation trick are especially worth studying as a pattern for constrained mechanical problem solving.

What Is A LEGO Typewriter

A LEGO typewriter, in this project, is a mechanical system that places preprinted or pre-marked tiles onto a plate to form characters. It does not transfer ink. Instead it dispenses 1×1 elements, or round tiles clipped to plates, aligns their rotation, and presses them into specific stud positions to create readable text.

How The LEGO Typewriter Works

The system works by converting a key press into three coordinated actions: a gravity-fed tile is released from a magazine, a ramp and arch rotate the tile into the correct orientation, and a stored-energy pusher (tensioned by a rubber band) slams the tile onto the target plate. The carriage then advances exactly one stud for the next character.

Dispensing And Magazine Mechanics

Each key corresponds to a short magazine that holds identical tiles. Pressing the key frees the bottom tile, which then travels by gravity. Magazine height and ramp angle determine reliable feed; too short and tiles jam, too tall and the build becomes bulky.

Orientation And The Arch Primitive

The arch-shaped element is the orientation primitive. At the ramp’s end it provides a single predictable contact that rotates the tile 90 degrees. This confined interaction reduces chaotic impacts into a repeatable alignment step and replaces more complex multi-axis mechanisms.

Pressing Force And Carriage Indexing

Energy is stored in rubber bands attached to beams. When released, the pusher slams the tile against the plate. The carriage movement is discrete, advancing one stud per character. Small frame flex or under-tensioning can produce faint presses or misalignment.

Advantages Of The Builder’s Approach

Using preprinted tiles and gravity simplifies the core problem: placement rather than ink transfer. This lowers parts cost, leverages predictable interactions like arches and gravity, and keeps the mechanism modular. The tradeoff is more attention to tolerance and manual steps such as reloading, which preserves approachability for makers.

LEGO Typewriter Versus Traditional Typewriters

Traditional typewriters transfer pigment via raised metal type and ink ribbons, relying on manufactured metal tolerances for consistent strikes. The LEGO approach replaces impact printing with placement of preprinted tiles, trading durability and throughput for accessibility, lower cost of parts, and the educational value of making mechanical logic from constrained components.

LEGO Official Set Compared To This Build

The official 2021 LEGO mechanical typewriter captured appearance and motion but did not place characters onto bricks. This build deliberately targets functional placement using different primitives, accepting extra mechanisms and manual steps to achieve actual typing output.

Motorized Or Automated Alternatives

Moving to motorized feeders or a guided carriage could improve repeatability but would increase complexity, cost, and footprint. The builder notes automation is possible but was avoided to prioritize compactness and mechanical clarity.

Who This Is For And Who This Is Not For

Who This Is For: makers, educators, and mechanical design enthusiasts who value clever use of parts, visible mechanical logic, and iterative problem solving. It is ideal as a demonstrator of constrained design principles and as a hands-on project that teaches tolerance management.

Who This Is Not For: people who need a practical text production tool. The system requires manual reloading, shows occasional misfeeds and underpresses, and produces throughput measured in minutes rather than pages per hour. It is a creative machine, not a daily driver.

FAQ

What Is A LEGO Typewriter?

A LEGO typewriter, in this context, is a build that places preprinted or pre-marked tiles onto plates to spell characters. It does not use ink transfer, instead relying on dispensing, orientation, pressing, and carriage indexing to form text.

How Does The LEGO Typewriter Work?

Keys release tiles from gravity-fed magazines. A ramp and an arch rotate the tile into the right orientation, and a rubber-band-tensioned pusher slams the tile onto the plate. The carriage advances one stud for each character.

Can A LEGO Typewriter Use Ink?

No. The project avoids ink transfer because LEGO tiles are flat decals, not raised metal type. The solution is to place preprinted tiles rather than attempt pigment transfer.

How Much Did The Parts Cost?

The builder chose round tiles that cost about €3 per pack. The only square 1×1 printed tiles mentioned appear in sets now selling for roughly €50 each, which would make a full character set substantially more expensive. An exact total for the whole build was not provided.

Is The LEGO Typewriter Practical For Writing?

Not for everyday writing. It requires manual reloading, occasional corrections for misfeeds, and produces text slowly. Its strengths are educational and demonstrative rather than practical throughput.

How Reliable Is The Mechanism?

The mechanism became repeatable after roughly three months of iteration, but it still shows occasional misfeeds and faint presses when tiles are not slammed firmly. Reliability is acceptable for demonstration but below the standard of manufactured typewriters.

Can The Reloading Be Automated?

Possibly, but the builder found early automated reload attempts unreliable and ultimately preferred a manual process. The design notes that automating reloads would trade footprint and complexity for convenience.

How Long Did It Take To Build?

The project was refined over roughly three months, including prototyping, a slow-motion camera discovery for the orientation trick, and a week of tuning to reach repeatability.

COMMENTS