When the first full-scale cyclocopter lifted cleanly in 2025 it did more than validate an old eccentric idea. It forced engineers to reframe what vertical flight can be when the rotor is not a ceiling fan but a ring of paddle-like blades that change pitch as they spin.

The real significance here is not simply that a strange machine flew. What matters is that a convergence of materials, motor technology, and ultra-fast control made a concept that failed repeatedly for a century cross a threshold from academic curiosity to operationally useful platform, provided certain hard constraints can be met.

Most people assume helicopters and multicopters are the natural endpoints of vertical flight. That assumption misses a class of capability. A cyclocopter hovers without tilting, translates sideways like a drone drifting through a warehouse, stops in mid-air without pitching, and rotates while staying upright. Those are not incremental advantages. They are a different set of tools for problems where tilt-based thrust and rotor downwash are liabilities.

What this article reveals early is simple: the cyclocopter is uniquely powerful inside a narrow envelope defined by scale, weight, and control responsiveness. Where those conditions hold it opens doors that helicopters and quadcopters cannot open. Where they do not, the technology remains an elegant footnote in aviation history.

What A Cyclocopter Is

A cyclocopter is a rotor configuration where a ring of paddle-like blades change pitch as they rotate to produce directional thrust. Instead of tilting the whole aircraft, the cyclocopter generates lateral forces through timed blade pitch changes, enabling level hover, sideways translation, and rotation about the vertical axis without reorienting the airframe.

The Paddle Wheel Idea That Refused To Be Ignored

In 1909 a Russian engineer named E.P. Sverchkov proposed something aviation pioneers did not know how to accept. Instead of spinning blades like a fan, Sverchkov imagined rotating cylinders lined with vertical wings, more like paddle wheels than rotors. Early attempts in the United States, Germany, and Russia produced dramatic mechanical failures.

The blades bent under extreme centrifugal forces, linkages tore themselves apart, frames twisted, and the craft that needed constant microadjustments had no electronics to do that work. By the 1950s the concept had become aviation folklore, an example of what not to do.

That odd history is essential because it explains why the cyclocopter was not merely a failed invention but a problem of physics plus missing technology. The physics were not wrong. The implementation tools were. The same idea later thrived in a different medium when engineers moved from air to water.

Why Water Loved It And Air Did Not

In the 1920s Austrian engineer Ernst Schneider adapted the cycloidal principle to ships with the Voith Schneider propeller. Rotating vertical blades whose pitch could be changed instantly gave tugboats and ferries maneuverability that traditional screw propellers could not match. Vessels could move sideways, spin on the spot, and hold position in heavy currents.

The takeaway is instructive. Water is dense and predictable. Those properties make control easier and forces gentler in ways that matter to rotating paddle arrangements. Air is thin and unsteady. Aerodynamic instabilities that are damped by water become explosive in the sky unless you can actively control them.

Put another way, the cyclocopter always needed two things to succeed in air: structural hardware that could carry the loads, and control systems that could make hundreds of micro adjustments every second. For much of the 20th century neither existed at the necessary performance and weight points.

How A Cyclocopter Works

The core mechanism is blade pitch modulation synchronized to rotation so that the instantaneous lift vectors add into a net force in any chosen horizontal direction. That requires fast actuators and precise timing so blade forces combine constructively rather than creating destructive vibration or unsteady moments. Control bandwidth is therefore central to stable flight.

The Tech That Finally Moved The Needle

What changed in the 21st century was not a single breakthrough. It was a set of enabling technologies that collectively closed the gap between a brittle idea and a functioning aircraft.

Materials And Mechanics

Modern carbon fiber composites and advanced linkages let designers make rotors that are both light and strong. The historical failure mode for cyclocopters was mechanical: centrifugal forces and aerodynamic loads bend blades and shred linkages. Today those forces can be managed through materials with strength-to-weight ratios that did not exist a few decades ago.

Quantified context helps here. Cyclotec, the Austrian team that focused on the rotor itself for more than 15 years, landed on a full-scale vehicle mass near 340 kilograms for its first flight test platform. Small prototype efforts have operated at a few tens of grams, so moving from gram scale to hundreds of kilograms increases absolute loads by orders of magnitude and multiplies the demands on structural components.

Controls And Miniaturization

Fast electric motors, high bandwidth actuators, and microprocessors capable of making hundreds of adjustments per second turned the problem of instability into one of control design. The first untethered cyclocopter model from Northwestern Polytechnical University in 2011 proved the idea at a modest size. Labs at Texas A and M and UC Berkeley showed how responsive actuation and control algorithms could tame gusts that would flip conventional multirotors.

What becomes obvious when you look at the experimental record is that smaller rotors often perform better because airflow is comparatively smoother and vortex interactions behave more favorably. That is why many early successful demonstrations were at tiny scales, including a model that weighed just 29 grams, lighter than a golf ball.

Blackbird And The 2025 Moment

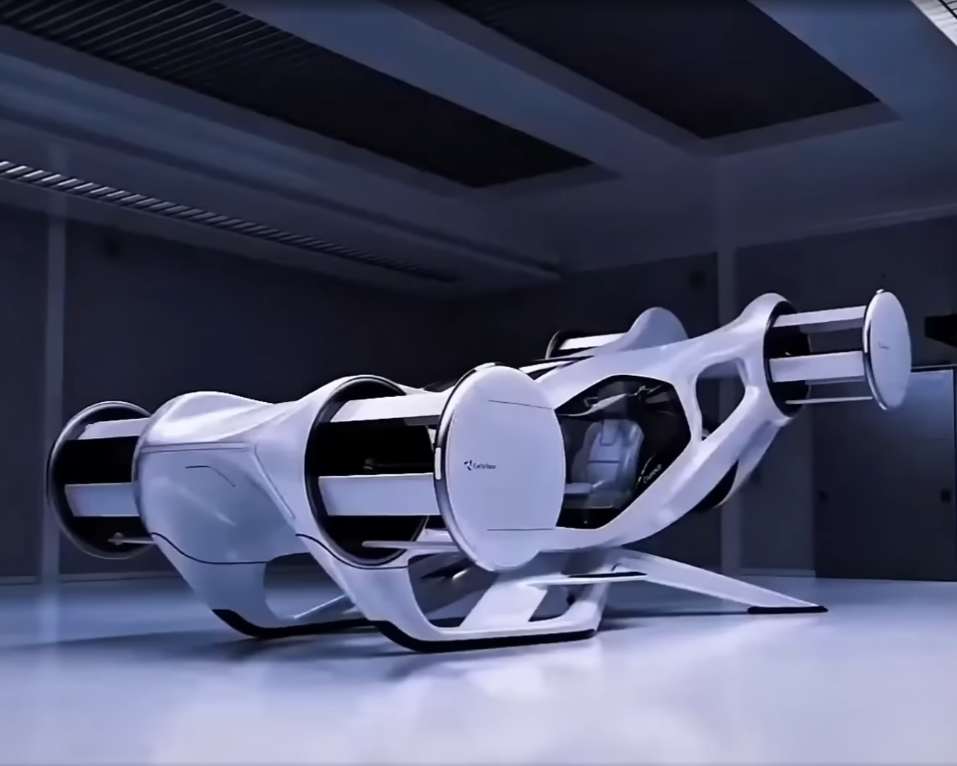

Austrian company Cyclotec chose a conservative path. Rather than rush to build a complete aircraft, the team spent more than 800 test flights refining blade shapes, linkages, actuators, and the carbon fiber components that carry load. The result was Blackbird, a 340-kilogram cyclocopter that completed its first full-scale test flight in 2025.

That flight did what small prototypes had hinted at. Blackbird rose smoothly, hovered without tilting, translated sideways, rotated precisely while staying upright, and came to a controllable stop in mid air. For the first time a large cyclocopter demonstrated the maneuver set that advocates had promised for a century.

The cyclocopter is not a better helicopter; it is a different tool with a narrow set of superpowers tied to a brutal scaling penalty.

From an editorial standpoint, that sentence captures the tension that will determine adoption. Blackbird showed capability. Whether that capability becomes a common option depends on material limits, energy density, and cost economics.

Cyclocopter Vs Helicopter And Multirotor Alternatives

Comparison matters because operators choose platforms against concrete constraints. Helicopters deliver proven payload, endurance, and established certification pathways but require tilt and produce large rotor discs. Multirotors are simple and scalable at small sizes but suffer downwash and inefficient hover at larger scales. Cyclorotors trade those conventional advantages for superior lateral agility and level-hover in confined, gusty environments.

Key Decision Factors

When deciding between options consider these factors: mission duration, payload mass, operating environment, maintenance cadence, and certification burden. Cyclocopters excel in short-duration, confined, or aerodynamically complex missions. They lose ground where long endurance, heavy lift, or low-cost mass production dominate the decision.

Where Cyclocopters Fit And What Holds Them Back

There are domains where the cyclocopter is immediately compelling. Search and rescue teams struggle with chaotic winds and confined environments where tilt-based aircraft are dangerous or simply cannot hover precisely. Military reconnaissance benefits from quiet, precise maneuvering in urban canyons. Urban air mobility design studies are interested because a vehicle that does not need to tilt can reduce the footprint of approach corridors and potentially lower risks near buildings.

Use Cases

Think of a tide of applications defined by narrow spaces and unpredictable aerodynamics. A cyclocopter can thread between façades, hold position in gusty down drafts, or peek around obstacles without exposing a large rotor plane. For missions measured in seconds to tens of minutes, where endurance is not the primary driver, cyclocopters can offer mission effectiveness that traditional helicopters and multirotors cannot match.

Scaling Tradeoffs

The remaining constraint is weight and the physics of scale. Centrifugal and aerodynamic loads scale nonlinearly with rotor size and rotational speed. Doubling rotor radius or doubling operational power does not double stress, it multiplies critical loads in ways that demand heavier structures and stiffer actuators. That arithmetic is why success at gram scale did not guarantee success at professional aircraft scale.

Quantified examples from the technical record make the tradeoff concrete. Small cyclocopters at the university level operate in the tens of grams and demonstrate excellent gust tolerance. Cyclotec’s first full-scale demonstrator sits near 340 kilograms. Between those points the design must absorb increases in peak loads, require stronger linkages and actuators, and carry larger power systems. The energy density of current batteries and the mass of actuators push tradeoffs toward either heavier structures or reduced payload and endurance.

Cost is another boundary. The components that make cyclorotors feasible at scale are not cheap. High-performance composites, rapid-response actuators, and control electronics that run high-frequency loops can push production costs into the hundreds rather than the tens of thousands of dollars per vehicle in small series runs. Mass production and standardized components could lower those numbers, but only if demand justifies the investment.

What Engineers Will Watch Next

Two constraints will decide whether cyclocopters remain a niche or become part of mainstream vertical flight: improvements in materials that reduce structure mass for given loads, and energy systems that increase specific energy without adding prohibitive weight. Advances in motors and actuators that raise bandwidth without commensurate mass increases will unlock better performance at larger sizes.

There is also an adoption constraint that is not purely technical. Operators have long training pipelines for helicopters and multirotors. Introducing a new flight regime with different failure modes means rebuilding procedures, certification pathways, and safety cases. Those processes are time-consuming and expensive, and they will influence which markets adopt cyclocopters first.

Maintenance is another practical limit. Complex linkages and high-cycle actuators surface wear sooner than static components. If rapid response mechanisms need service after hundreds of hours rather than thousands, operational cost models will favor conventional designs for high utilization scenarios.

Why This Matters Beyond A Single Machine

The cyclocopter story reframes how engineering breakthroughs happen. It is rarely a single innovation. It is the slow alignment of materials, controls, and systems engineering until an old idea becomes new again. That pattern repeats across transport technologies, from electric cars to unmanned systems.

What matters for cities, rescue agencies, and defense planners is not whether cyclocopters are universally better. It is whether their distinct advantages align with the right missions where the scaling penalties are manageable. That alignment is what turns a laboratory novelty into a platform with real impact.

A look ahead suggests staged adoption. Expect hand-launched and small tactical cyclorotor vehicles to appear first where their maneuvering superiority is decisive and endurance demands are modest. Larger manned or heavy lift cyclocopters will require either a leap in structural mass efficiency or an improvement in energy density to be practical at scale.

The cyclocopter finally works, and that success is less an endpoint than the opening act of a longer engineering conversation. The question is not whether it can fly. The question is where its unique abilities are worth the cost and the engineering tradeoffs necessary to scale them.

Imagine the neighborhoods, disaster zones, and ship decks that suddenly have an aircraft that can hold position in a thermal, slip sideways without reorienting, or rotate in place to inspect a façade. Those are not small advantages. They are mission shapes that could change how missions are designed and which tools are used.

The next decade will show whether cyclocopters become a ubiquitous tool in the vertical flight toolbox or a brilliant solution reserved for specific, high-value use cases. Either way, watching a century-old idea finish its arc into practical hardware feels like an unusually clean example of the patient work engineering requires.

Looking forward, the story of the cyclocopter will be about who solves the scaling equation first, and how that solution reshapes the tasks that vertical flight can do safely and reliably in complex environments.

Who This Is For And Who This Is Not For

Who This Is For: Operators needing precise, level hover and lateral agility in confined or aerodynamically complex environments. Examples include short-range search and rescue, urban reconnaissance, and specialized shipboard operations where sideways translation and zero-pitch inspection are decisive.

Who This Is Not For: Long endurance transport, heavy lift cargo, or low-cost high-utilization services where existing rotary wing or multirotor architectures deliver better economics, established certification, and lower maintenance demands.

FAQ

What Is A Cyclocopter?

A cyclocopter is an aircraft using a ring of paddle-like blades that change pitch as they rotate to generate directional thrust without tilting the airframe. It enables level hover, lateral translation, and rotation about the vertical axis through timed blade pitch modulation.

How Does A Cyclocopter Differ From A Helicopter?

Unlike a helicopter that tilts its rotor plane to move, a cyclocopter produces horizontal forces by varying blade pitch during rotation. That lets it hover level while translating sideways or rotating in place, at the expense of more complex linkages and control requirements.

Why Did Cyclocopters Fail Historically?

Early attempts failed because materials and control systems could not handle the centrifugal and aerodynamic loads, and mechanical linkages fatigued or failed. The physics were sound, but the implementation tools were insufficient for airborne scale.

What Changed To Make Them Work In 2025?

A convergence of stronger, lighter materials, faster electric motors, high bandwidth actuators, and control electronics capable of making hundreds of adjustments per second enabled a full-scale demonstrator to fly in 2025.

Are Cyclocopters Better Than Multirotors?

They are different. Cyclocopters offer superior lateral agility and level hover in confined, gusty environments. Multirotors remain simpler, cheaper at small scale, and often more practical where endurance, payload, or cost are primary drivers.

What Are The Main Limitations Of Cyclocopters?

Scaling penalties tied to centrifugal and aerodynamic loads, actuator and linkage mass, energy density limits, higher cost components, and potentially increased maintenance are the primary constraints.

Who Should Consider A Cyclocopter?

Teams with missions that require precise position keeping, sideways translation without reorientation, or rotation in place in cluttered or gusty environments should evaluate cyclocopters. Organizations prioritizing long endurance or heavy lift should look elsewhere.

Will Cyclocopters Replace Helicopters?

Uncertain. Replacement is unlikely across the board. Widespread adoption depends on advances in materials, energy systems, and certification pathways that overcome current scaling and cost penalties.

COMMENTS