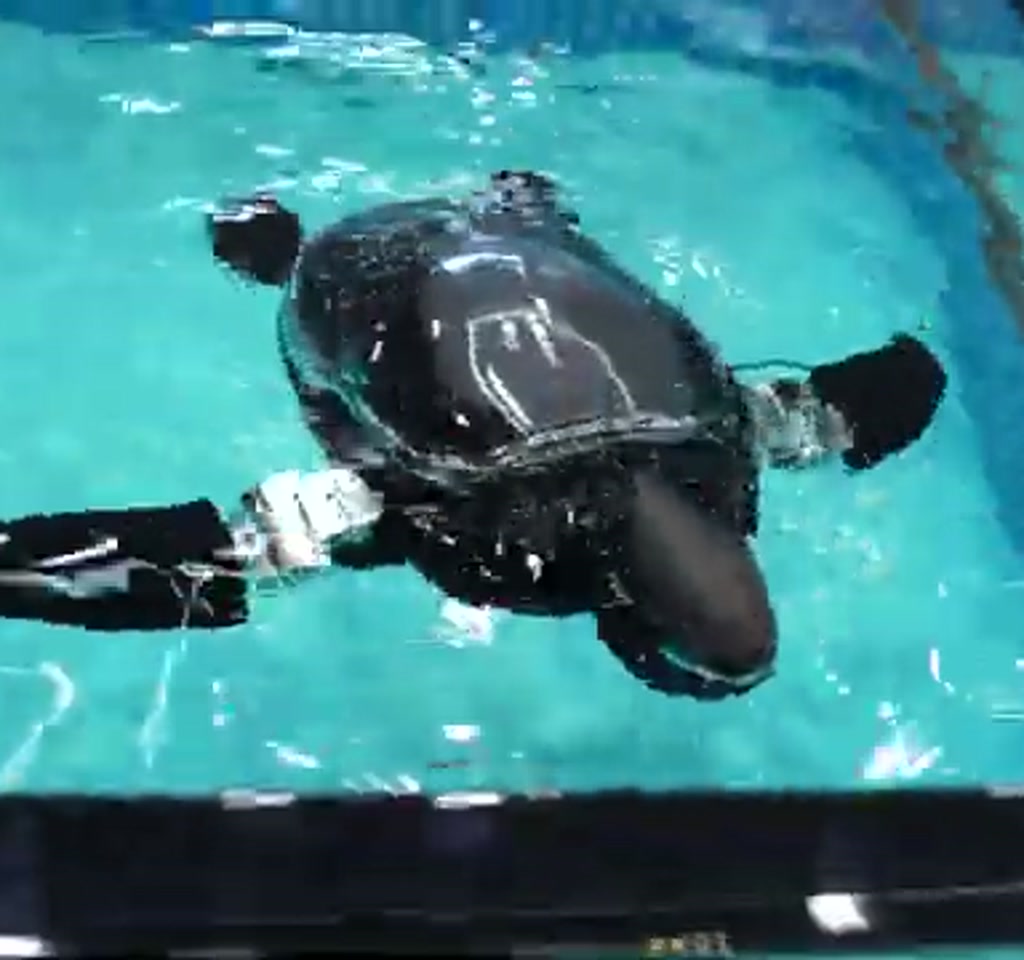

Beatbot’s Aquatic Roboturtle, nicknamed Tortini, lands immediately as a different kind of seabound idea. It is not a pool-cleaning gadget dressed up as a novelty. It is intentionally designed to look and move like a sea turtle so it will be less intrusive in natural habitats and more likely to be accepted by the animals and ecosystems it studies.

The real significance here is not just that a robot mimics a turtle. What actually determines whether Tortini matters is the balance between stealth and systems constraints. The turtle form gives access to behaviors and observation windows that conventional underwater drones struggle to achieve. That advantage only holds up when engineering boundaries for corrosion, power, and data transfer are solved within practical cost and operational limits.

There is another early insight worth stating plainly. Most people imagine autonomous ocean robots as fully connected, always streaming platforms. Tortini exposes an alternative pattern: local data collection with periodic, surface-based communication. This approach widens what is feasible in terms of stealth and longevity, but it puts hard limits on bandwidth, latency, and mission profiles.

What becomes obvious when you look closer at Tortini is that its promise is less about replacing boats and more about adding a new, lower impact instrument to the marine researcher toolkit.

Its design choices reveal the tradeoffs that will govern whether it becomes routine gear for biologists or an intriguing prototype that never scales. The rest of this article explains how Tortini is intended to work, the engineering tensions that define its usefulness, and the realistic timeline and cost constraints that will shape its deployment.

Why The Turtle Form Is More Than A Costume

Designing a robot to resemble a sea turtle is not an exercise in aesthetics. It is a deliberate attempt to reduce behavioral disturbance. Animals respond to shape, movement, and acoustic signature. A machine that looks and moves like a turtle is less likely to trigger avoidance behaviors in fish, to scare foraging species away, or to alter coral-associated microhabitats during observation.

Behavioral Stealth

The behavioral advantage is the primary operational insight. Tortini’s turtle-like motion and silhouette aim to create an observational platform that can swim among schools of fish and around reefs without changing the very phenomena researchers want to study. For migration and reproductive pattern studies, that matters. Observations made from noisy or obviously foreign platforms can bias results by shifting animal behavior toward refuge or flight responses.

The detail most people miss is that stealth has second order benefits. Reduced disturbance can mean longer observation windows per deployment and less need for post hoc behavioral correction in datasets. That increases the value of each mission day when compared to short, conspicuous visits by boats or conventional remotely operated vehicles.

Design Tradeoffs

Biomimicry imposes constraints. A turtle-shaped hull limits internal volume for batteries, sensors, and mechanical systems. That forces tradeoffs between the sensors Tortini can carry, the energy available for propulsion, and the time it can spend underwater between recharges. Hydrodynamic efficiency, stability, and silent propulsion mechanisms all compete for the same real estate inside the shell.

This only becomes interesting when you look at mission design. If a research team needs continuous, high-resolution video from a moving vantage point for many hours, a larger platform with bigger batteries and comms gear may be preferable. If the goal is intermittent, minimally invasive sampling across wide areas, a turtle-like robot offers a unique advantage because it can observe behaviors that would otherwise be masked by the presence of human-led craft.

How Tortini Collects Scientific Data

Tortini is being pitched as a mobile marine researcher rather than a maintenance gadget. According to the developers, its mission set includes tracking different types of fish and schools of fish, studying migration and reproductive patterns, monitoring coral reef status, and sampling water quality. Those objectives define the sensor suite and data strategies the robot must support.

Typical sensor types for these tasks include optical cameras, acoustic sensors, and water chemistry probes. Cameras and hydrophones let researchers observe behavior and soundscapes, while probes measure temperature, salinity, pH, dissolved oxygen, and turbidity to assess water quality. These are common sensing modalities in marine autonomous platforms, and they are likely to be central to Tortini’s payload.

Data will be collected locally while the robot is submerged. Wireless underwater communication is constrained by physics and remains difficult at anything beyond low bandwidth levels. The team behind Tortini plans for the robot to surface for recharging and then transmit accumulated data to researchers on boats or other stations. That approach shifts design emphasis toward robust onboard processing and storage.

Onboard Storage And Processing

Because Tortini does not rely on continuous wireless links underwater, it needs to decide what to store, compress, or discard. High-fidelity video can generate data volumes ranging from multiple megabytes to multiple gigabytes per hour depending on resolution and compression settings. That makes selective recording, event-driven captures, and onboard summarization important.

This tradeoff shapes mission duration and power consumption. Recording and processing are energy-intensive. The choice between storing raw data for later analysis and pre-processing data into telemetry or feature summaries determines how long Tortini can operate between recharges and how much post-mission analysis will be required.

Hard Limits: Corrosion, Communication And Power

Building a robot for salt water brings three constraints into sharp focus: corrosion, communication, and power. Each one is a boundary condition on what the device can accomplish in routine deployments. The project is in its second year of development and the team expects a deploy within the next five to 10 years, giving them time to address these issues but also placing practical expectations on their engineering choices.

Corrosion is a top technical hurdle. Saltwater is an aggressive electrolyte that speeds material degradation through galvanic reactions. Over time, exposed metals and connectors fail unless they are specially protected. The challenge is not theoretical. It is a maintenance reality that influences materials selection, coating technologies, sacrificial anodes, and seal design.

To give quantified context, corrosion-related maintenance often becomes significant within months for unprotected systems and can be pushed out to years with robust sealing and expensive materials. That means lifecycle and service intervals are not negligible. For research programs, the tradeoff becomes whether to use cheaper units that require frequent maintenance, perhaps every few months, or invest in more expensive builds that can reliably operate for several years between major overhauls.

Communication constraints are the other hard limit. Underwater wireless communication is typically acoustic and the available bandwidth is often measured in kilobits per second rather than megabits per second. That is adequate for telemetry, short status packets, or low-resolution acoustic streams, but not for continuous high-definition video. This is why Tortini’s designers plan to rely on surface-based transfers during recharge windows.

From an operational viewpoint, that implies two things. First, mission profiles need to accommodate surfacing frequency and recharging logistics. Second, remote real-time control or continuous live-stream monitoring is not realistic for data-heavy tasks. Instead, Tortini will operate more like a field recorder that occasionally syncs its content to shore or to a vessel.

Power and recharging complete the triangle of constraints. Battery capacity, propulsion efficiency, and onboard electronics determine how long Tortini can remain submerged. The developers acknowledged that the robot must surface to recharge. That suggests mission lengths that are likely to fall within a range of hours to days between recharges, depending on the activity level, sensor load, and whether energy-saving modes are used.

Deployment Timeline, Costs, And Operational Realities

The team states that Tortini is in year two of development with a deployment horizon of roughly five to 10 years. That is a realistic window for a novel marine robotics platform that needs to mature mechanical, electrical, materials, and software subsystems and pass environmental testing and regulatory review.

Cost is another boundary. Marine research robotics are not cheap. For context, development and per-unit production typically scale into the hundreds of thousands rather than the tens of thousands of dollars when long-term corrosion resistance, robust sensors, and field serviceability are required. That places Tortini in the realm of institutional procurement for universities, research institutes, and government agencies unless the team finds ways to drive unit costs down through volume or modular design.

Operationally, there are additional costs to account for. Deployments will commonly need support from boats or dockside stations for recharging, data collection, and possible retrieval. Even if Tortini is engineered to be largely autonomous and robust, field missions incur logistical expenses that include vessel time, maintenance crews, and data processing labor.

Adoption friction also arises from permitting and ethical considerations. Studying migration and reproductive patterns often requires permits, ethical review, and coordination with local conservation authorities. A platform designed for minimal intrusion reduces some ethical friction but does not eliminate the need for oversight, especially in protected areas or when tracking endangered species.

What Determines Whether This Works

Two major variables will determine Tortini’s practical success. The first is materials and sealing technology that keep corrosion and biofouling from degrading performance within acceptable maintenance intervals. The second is energy and data strategies that balance mission duration against the need to surface and offload data.

Small changes in either variable can shift the robot from useful to fragile. If battery life cannot support the desired observation window, missions must be shorter or less sensor-intensive. If communication remains limited to short bursts, then near-real-time interventions become impossible and researchers must rely on post-mission analysis. These are not fatal flaws. They are conditional thresholds that define what Tortini can contribute to ocean science.

Where Tortini Fits In The Bigger Picture

Tortini sits at the intersection of a few broader trends: the push for less invasive ecological monitoring, the move toward distributed long-duration sensing, and the maturation of biomimetic design in robotics. It is not a single silver bullet. Instead, it is an instrument for specific kinds of questions where being unobtrusive matters more than streaming endless high-resolution video.

Putting a robot turtle alongside other tools makes the research toolkit more versatile. For example, satellites provide synoptic, large-scale views of sea surface conditions. Manned or unmanned vessels can collect high-bandwidth sensor suites when disturbance is acceptable. Tortini can fill the niche of up-close behavioral observation without large ship presence, particularly in sensitive coral reef environments or when studying animal interactions that would be altered by human presence.

From an editorial standpoint, the most interesting implication is the methodical tradeoff between presence and access. Tortini suggests researchers are willing to trade continuous connectivity for authenticity of observation. That tradeoff will influence how field studies are designed and how data is interpreted.

It will also change the economics of long-term monitoring. A community of low-impact mobile recorders could reduce the need for constant human presence and repeated intrusive surveys. But real cost savings will only materialize if per-unit costs and maintenance burdens can be kept low enough to allow meaningful scale, perhaps tens to hundreds of units per program, rather than a handful of highly specialized pieces of equipment.

Technical Roadmap Signals

The current statement from the developers that Tortini is in prototype and expected to deploy in five to 10 years carries implicit roadmap signals. The team is prioritizing corrosion mitigation, reliable surfacing and docking mechanics for recharging, and data handoff protocols. Those are sensible near-term priorities because solving them unlocks the core mission of long-term, low-impact observation.

What to watch for as development progresses includes demonstrated endurance runs in saltwater for months rather than days, validated corrosion control methods, and proofs of concept showing meaningful biological observations gathered with minimal disturbance. Milestones like these will turn conceptual promise into operational reality.

The project also highlights a broader lesson. Creating tools that fit into natural systems requires engineering humility and a willingness to accept limits in exchange for novel observational angles. Tortini is promising not because it aims to out-engineer the ocean but because it chooses to be small and subtle within its operating envelope.

Tortini Versus Conventional Underwater Drones And Vessels

Comparison clarifies choice. Tortini favors stealth and low disturbance at the cost of bandwidth, continuous runtime, and interior volume. Conventional underwater drones and larger vessels offer more power, sensors, and communication capacity but are more likely to alter animal behavior and the environment they sample.

Observation Quality Versus Bandwidth

Tortini’s advantage is observational authenticity; it can get closer to animals without causing the same behavioral shifts. The tradeoff is data bandwidth. Acoustic links and surfacing transfer mean real-time, high-definition streaming is not the design intent. Where continuous, live video is essential, traditional drones or ship-based systems remain the practical choice.

Cost And Logistical Differences

Operational costs differ too. Larger platforms carry higher initial costs but may lower per-mission labor and data constraints depending on the study. Tortini’s lower-impact profile could reduce repeated human visits, but only if maintenance and unit costs are kept manageable for programs that might want many units in the field.

Who This Is For And Who This Is Not For

Who This Is For: Tortini is best suited to researchers who prioritize undisturbed behavioral observation, long-term distributed monitoring at limited bandwidth, and studies where human presence would bias results. Conservation programs, coral reef ecologists, and behavioral biologists studying sensitive species are natural fits.

Who This Is Not For: Tortini is not the right tool when continuous high-definition live streams, heavy instrument stacks, or real-time remote intervention are required. Projects that need long, uninterrupted video or very high telemetry bandwidth should prefer larger autonomous underwater vehicles or ship-based sensor suites.

FAQ And Practical Questions

What Is Beatbot Aquatic Roboturtle Tortini?

Tortini is a biomimetic, turtle-shaped research robot designed to observe fish, reef environments, and water quality by blending into natural habitats. It emphasizes low disturbance and local data collection with periodic surface-based data transfers.

How Does Tortini Communicate Underwater?

Underwater communication is expected to rely on low-bandwidth acoustic links while submerged, with higher-volume data offloads during surface surfacing and recharge windows. Continuous live high-definition streaming is not the intended mode.

Is Tortini Designed To Replace Research Vessels?

No. The project is positioned as a complementary instrument that expands observation options, not as a replacement for boats or larger unmanned systems that carry heavier sensors and offer larger power budgets.

What Are The Main Technical Challenges For Tortini?

Key challenges are corrosion resistance and sealing, power and battery life that determine mission duration, and data strategies that balance onboard processing with limited communication windows. These constraints shape cost and maintenance expectations.

When Will Tortini Be Deployed?

The developers indicate Tortini is in year two with an expected deployment horizon of roughly five to 10 years. This timeframe allows for maturation of materials, endurance testing, and regulatory steps.

How Much Will Tortini Cost?

Exact pricing is not provided. The article notes marine research robotics that require long-term corrosion resistance and robust sensors typically scale into the hundreds of thousands of dollars per development and per-unit production when built for long-term field use.

Can Tortini Operate In Protected Or Sensitive Areas?

Yes, but deployments will likely need permits and ethical review. Tortini’s low-impact design reduces disturbance-related concerns but does not remove oversight requirements for protected or endangered species.

Does Tortini Offer Real-Time Control?

Real-time, remote interventions for data-heavy tasks are limited by communication bandwidth. Tortini is intended to act more like a field recorder with occasional syncs rather than a continuously piloted live-streaming platform.

COMMENTS